Comics have often been used to instruct audiences about social and political issues, including those related to concepts of racial identity. Some target adult readerships. Others children. But many such comics have played a part in embedding ideas about racialised identities and structures. Though some of the works in this section fomented racism, often from a young age, other comics highlight both comics themselves and childhood as sites of struggle for ideas of race.

Breve guía técnica del dibujo popular is a manual produced in Lima in 1981 by Comisión Evangélica Latinoamericana de Educación Cristiana (CELADEC). In the introduction, it is stated that the material was conceived by the Equipo Pueblo Foundation of Mexico. This Christian organisation was established in that country around 1977 and was directed by Alex Morelli and Ángel Torres. This Mexican publication aimed to promote tools to improve graphic communication in communities. It sought to serve the most disadvantaged sectors in rural, Indigenous and marginalised urban areas. The organisation opted for the strategy of regionalisation and collaboration with the different Basic Ecclesial Communities, such as the one in Lima, to work from the perspective of the defence of the poor and social justice from a transnational religious perspective. The guide presents keys to the production of graphic materials: the function of the media, the explanation of how to work with visual resources, the characteristics of the use of drawing in print, layout and format, as well as tools for drawing people, scenarios and animals. Most of the representations have been standardised, without any particular ethnic specificity, nor the presence of Black populations.

Malena Bedoya

These cut-out masks belong to the themes and tropes of blackface minstrelsy, a white supremacist theatrical tradition of anti-Black racism created in the US in the XIX century, where performers darken their faces with black paint and pretend to act as Black characters. In systemic racism, which operates at all levels of society, from institutional and public to interpersonal and private, the indoctrination of racist values in children is key to perpetuating racial hierarchies and white supremacist ideologies. Through storytelling and play, children are socialized into normalizing and enacting racial violence. This example, and the one below, come from the early XX century mainstream Argentine and Colombian press, a mass media industry which, like others in the Western world, already operated under a systemically racist, whiteness-privileging paradigm.

Abeyamí Ortega

Children's sections in mainstream newspapers often featured deeply racist imagery, perpetuating harmful stereotypes, and reinforcing dehumanizing portrayals through the lens of white supremacy. In Latin American societies, where both light-skinned mestizo and whiteness privileging ideas are predominant, it was not very different. Here, two powerful institutions converge to educate and reinforce the violence of racism in children: the media and the family. Parental collaboration is needed to enable children to access the blackface mask.

Abeyamí Ortega

Mojicón is a comic strip created by Adolfo Samper for the Colombian newspaper Mundo al Día between 1924 and 1938. This character is a white-mestizo middle-class boy who plays with his street friends, who are depicted wearing espadrilles, ruanas, torn trousers or barefoot. This attire is associated in the comic with the Indigenous, the Black, poverty and non-urban geographies. According to Robin Bernstein, childhood innocence is never innocent and is always racialised. In this episode, we see how racist representations operate in the construction of the characters and their interactions. Clarita is a Black woman whose name alludes to whiteness. Thus, the artist uses the diminutive as a form of affection and at the same time sarcasm, as he transforms its meaning into a positive emotion while showing us the black colour of her skin. Mojicón wants to have his way in this scene and decides to paint his and his friend's faces with charcoal to look like Clarita's children and thus enter the cinema. This exercise in blackface, as a racist disguise, seeks to generate humour in the readers in the face of what appears to be an innocent childish prank.

Malena Bedoya

Boquellanta –a racist term to refer to a person with thick lips– is the name of a comic strip and its main character, an Afroperuvian child, created by Peruvian comics artist Hernan Bartra, published in the newspaper Útima Hora from 1953. Boquellanta exemplifies how racism can be expressed in ambivalent ways. Boquellanta is represented as smarter, wittier, more agile, and more romantically desirable to women than his white and light-skinned-mestizo counterparts, yet openly racist visual and textual depictions, including Boquellanta’s family, are deployed in different episodes of the comic strip. These politics of representation relate to Peter Wade’s findings regarding ambivalence in anti-Black representations in Argentina’s 1920’s La página del dólar. In this kind of ambivalent racism, negatively racialised characters are represented in openly racist yet ambiguous ways, conveying “a dual dynamic of simultaneous subordination and limited inclusion of Blackness in Latin America” (Wade 2023: 1). Boquellanta indisputably constitutes a racist representation, and the racism is deployed in combination with features that present Black characters in this comic strip as fit and capable yet still are subjected to dehumanised representations.

Abeyamí Ortega

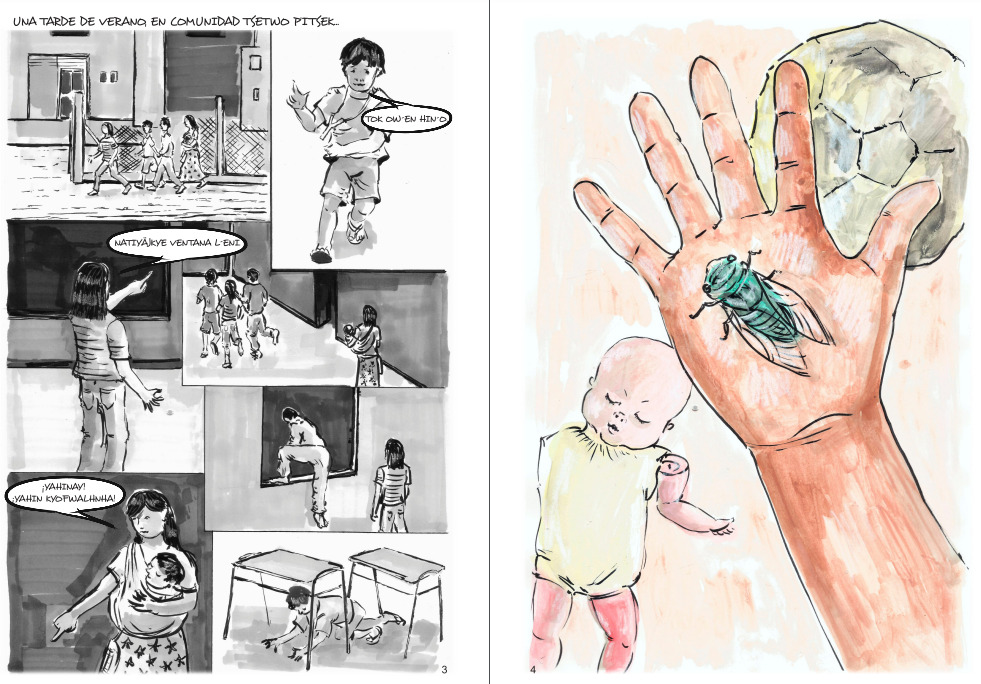

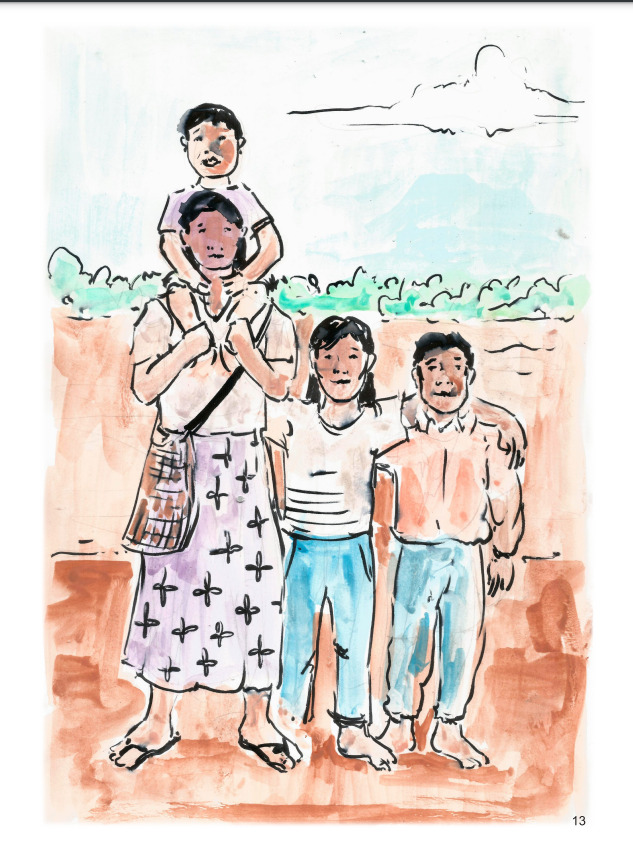

The creators of this comic, Osvaldo, Pamela, Lourdes and Luis, are part of the Kalay'i collective. In Nopeyakas N'äyhäy the Wichí characters have agency over the content they want to share with us, reclaiming their right to exist and expressing themselves on their own terms. Life is not easy for the Wichí due to the inequalities resulting from colonization. Their exclusion form society can be evidenced in the difficulties the Wichí have in accessing state institutions due to policies that do not recognize the cultural diversity of the region.The comic also allows us to fly over moments and spaces of the Wichí community, their communal practices linked to the river, and their territory, abundant in natural resources for survival as well as human and non-human allies.

Catalina Delgado Rojas