Colombia

Colombia has the third largest population in Latin America and, according to its 2005 census, it has one of the largest Black populations in the region, both numerically and proportionally: about 4.5m people self-identified as Black, around 11% of the total. The country is also unique in having an entire region - the Pacific littoral - where over 80% of the population is Black. Despite this, the presence of Black people in Colombia has been historically marginalised. Even today, after 30 years of state multiculturalist policies that have increased recognition to some extent, they are still marginalised in a nation characterised by marked racial inequality and racist attitudes and practices.

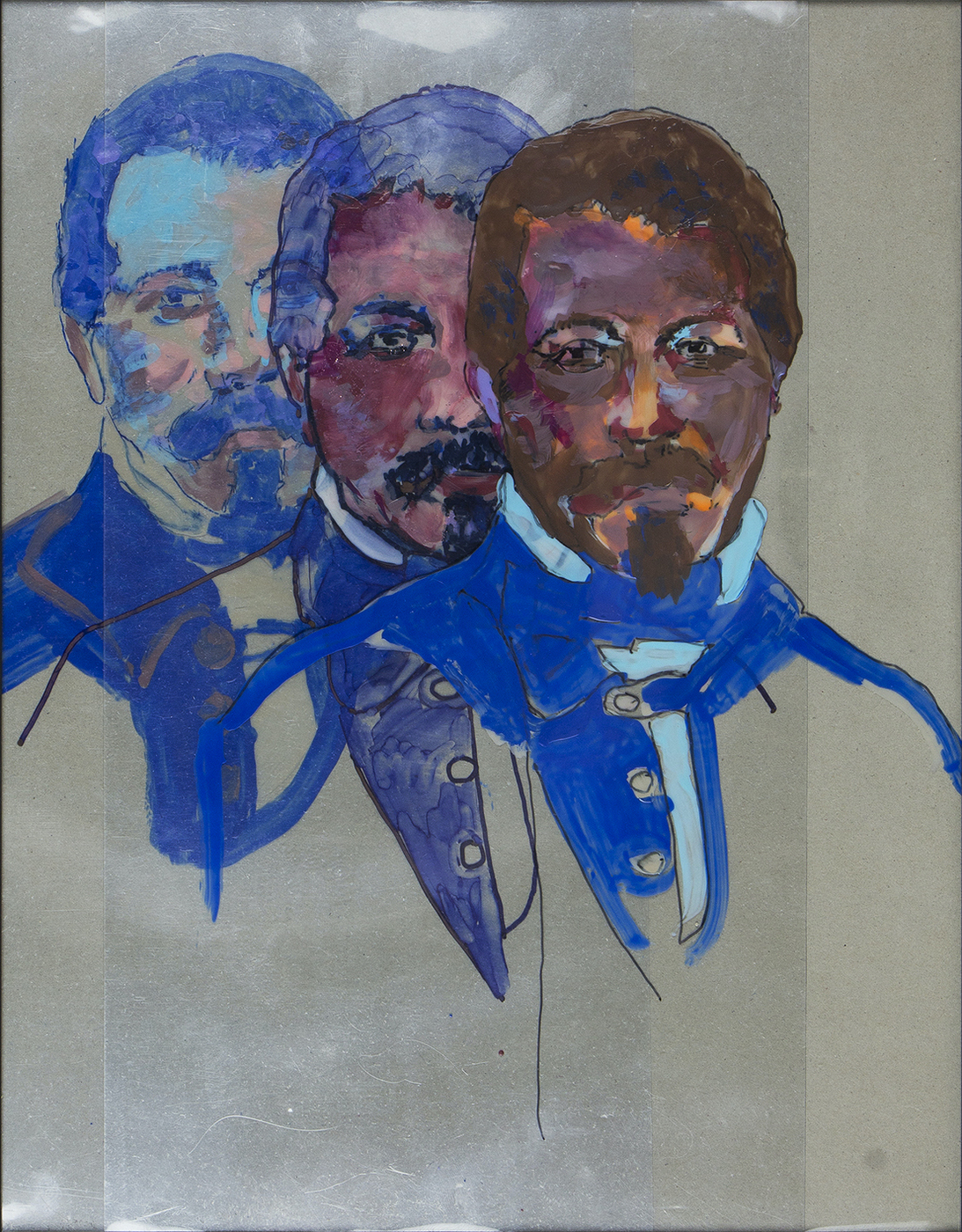

Black people have occupied a marginal position in the Colombian art canon. The representation of Black and Indigenous populations became fashionable in the mid-twentieth century, in the hands of well-known non-Black and non-Indigenous artists, shaped by a marked exoticism and primitivism. However, the presence of Black artists was ignored and made invisible.

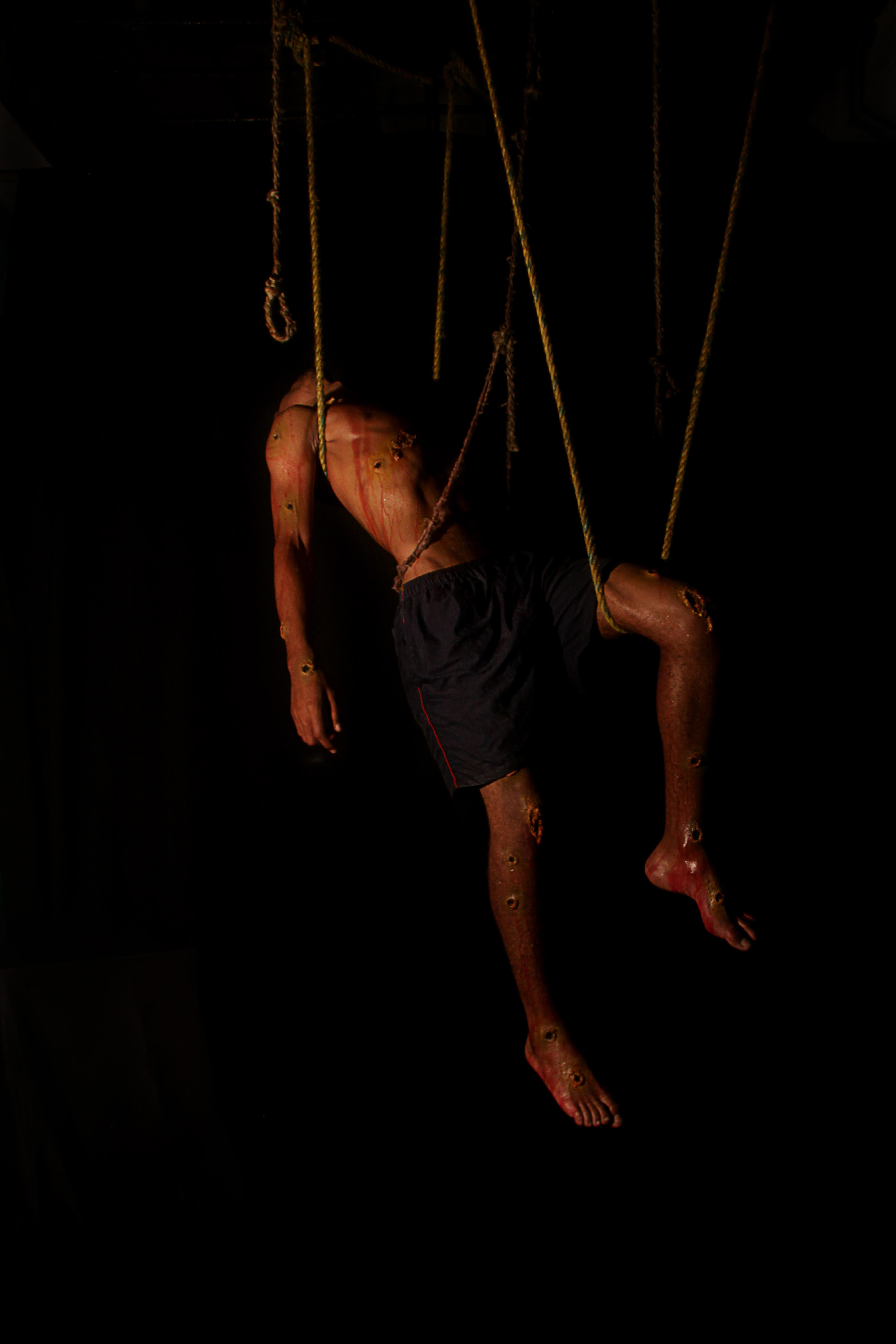

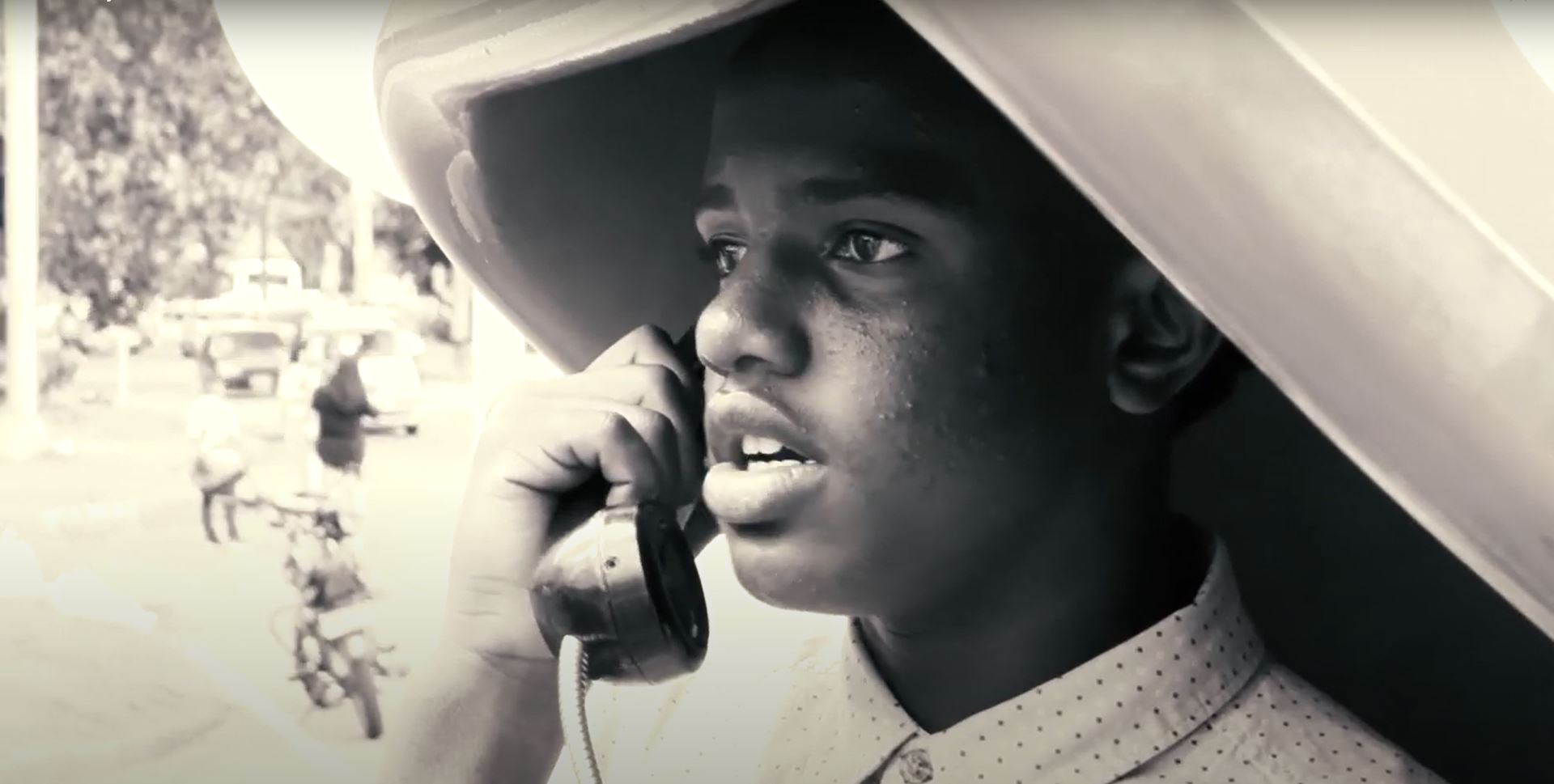

The contributions of Black and Indigenous people in Colombian art can be traced back to the end of the 18th century, in plastic arts, and to the 19th century in literature. However, they only became better known on the national art scene in the 20th century. In these artistic expressions, references to racism at times overlapped with allusions to popular culture or identity affirmation within the framework of multiculturalism. However, starting in the 2000s, several Afro-Colombian artists - and others outside that group - began to address racism more directly by using everyday experiences as reference points for their artistic creations. The artists also introduced forms of self-representation in art. Using diverse expressive forms, a narrative emerged that dismantled the stereotypes of Afro-descendants and combated the rejection of racialized working-class sectors. These artistic practices constructed more balanced versions of the history of Black people and placed racialised subjects at the centre of the art landscape, promoting Afro-referentiality, inscribing themselves in Afro-diasporic struggles and enhancing Afro aesthetics as a place of political enunciation. The fight against racism in art in Colombia also questioned the colonial legacy and the preeminence of whiteness in the social order.

The Colombian artists in this section of the exhibition belong to local and translocal networks of activism, feminism based on decolonial perspectives, and community and participatory artistic practices. Most of them have established artistic collaborations with each other, despite being located in different regions of Colombia. They are also subjects who have experienced racialization in their bodies and the effects of the stigma of "race" as a label that always accompanies them. Their artistic practices can be described as politically committed to structural social transformation and they reflect, more or less explicitly, on the effects that racism has on a daily basis on bodies, people, communities and urban and rural territories. These artistic pieces are enunciated using heterogeneous aesthetic languages that mobilise emotions and affectively challenge audiences using dance movements, Afro-Caribbean musical sounds, photographic, graphic and audiovisual images, portrait, video, and the musicality of poetry that evokes an Afro-religious universe. Among the narrative strategies that artists deploy in their artistic practices are: to question, move, annoy, satirise, outrage, criticise, dignify, deny and document experiences.

Finally, the pieces presented here belong to artists who have sought to renew Afro and decolonial aesthetic languages. In a self-conscious way, their artistic practices break into hegemonic spaces of art in Colombia with unconventional proposals that seek to "affect" the established consensus on Afro identities and their ways of being and living in society. For this reason, artistic practices are based on participatory action-research processes and methods that include the documentation of Afro-descendant religiosities and traditional dances, delving into family archives, and the investigation of other official historical sources to explore the contributions of Black people to art and the nation. These artistic practices also support processes of reconstruction of community memory through photography and video, and thus help to promote the affirmation of racialised difference in more inclusive terms.

Carlos Correa, Peter Wade